IMPROVING MEASUREMENT OF WOMEN’S WORK PARTICIPATION: SENSITIVITY OF WORK PARTICIPATION RATES TO SURVEY DESIGN

By Neerad Deshmukh, Sonalde Desai, Santanu Pramanik and Dinesh Tiwari

National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER)

The process of improving measurement of women’s work participation largely depends upon all responses to the following question: Are estimates of women’s employment more sensitive to question wording than men’s? This is the question that the Delhi Metropolitan Area Study (DMAS) seeks to answer. In early 2019, as part of DMAS, 5,252 households were administered a questionnaire that suggested two approaches to examine how the definition of work can change labor force participation rates, particularly for women. The first was an approach used by the National Sample Survey (NSS) whereas the second added a blended set of questions that widened the scope of what counted as work. This study has information on 27,428 individuals residing in 12 of 31 districts in the Delhi National Capital Region (NCR) spanning four States, and covering both urban and rural areas.

At the start of the interview, the respondents were asked the following status-based questions:

- What was the primary activity status of different household members over the past 12 months?

- What is the secondary activity that they undertook which lasted for at least 30 days?

These questions are identical to the questions included in the NSS (NSSO 2019). However, they were followed up by questions asking the respondent to identify different sources from which the household derived its income, and after each source of income was mentioned, the questionnaire asked which household members participated in this activity and how much time they committed to it.

These activity-based questions capture data to address the following questions:

- Who are the household members that worked on the family farm?

- Who are the household members that took care of livestock?

- Who are the household members that participated in the family business?

- Who are the household members that participated in farm or non-farm wage work?

The difference between status-based questions included in the labor force surveys and activity-based questions included in the experimental approach lies in ensuring that the interpretation of what counts as “work” is not left to individuals but is rather explicitly defined.

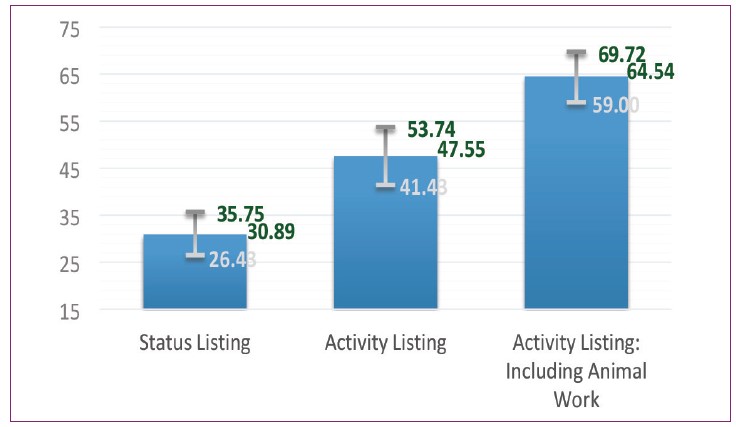

Results: Labor force status questions identify fewer women as working than questions that ask about participation in specific activities.

The difference in the proportion of women identified as working varies drastically depending upon the wording of the question. Among the DMAS sample of 21-59-year-olds, only 28 percent of the women are identified as working, using either the usual principal or subsidiary status questions. However, when asked about participation in farming, non-farm business, and wage work, the proportion increases to about 33 percent. When questions about individuals caring for livestock are added, the proportion increases to 44 percent. This suggests that respondents do not see women as being in the labor force when they are asked about their employment status, but when asked about specific activities, they are more likely to report women’s participation in these activities.

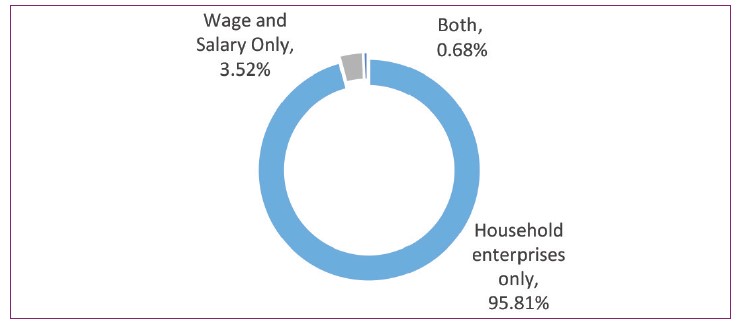

This difference is particularly large for work on family farms and in caring for livestock, which consequently affects rural estimates more than urban estimates.

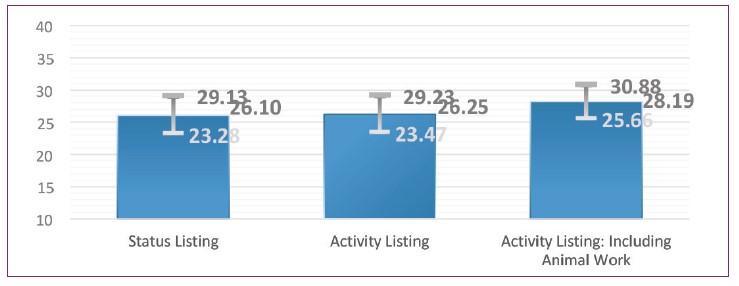

Much of the overlooked work consists of women’s work on family farms and caring for livestock. This suggests that omission of women’s work is a problem particularly affecting rural areas. In the DMAS urban sample, the difference between activity and status listing is barely 2 percentage points for urban areas but as much as 34 percentage points for rural areas. For rural women, farm work and caring for livestock merges into their day-to-day household activities and informants often do not consider it as “work”. It is only when the respondents are explicitly asked about participation in these activities that we are able to get estimates of women’s contributions to these sectors.

Underestimation of work participation is limited to women and does not affect estimates of men’s work.

A substantial body of literature on gender and development (Banerji and Jain 1985) notes that gender norms dictate that male farmers are called farmers, and women farmers are often dubbed as family helpers. Our results from DMAS support this finding. Most of the increase in employment using activity listing takes place for women. Among the DMAS sample of urban and rural respondents, when precise questions were asked about participation in specific activities, the worker to population ratio for women increased by 16 percentage points, with the increase for rural women being far larger than that for urban women. However, the work participation rate for men declined slightly by 0.5 percentage points. Thus, while men are assumed to be working by default, women are assumed to be out of the labor force until specific questions force respondents to revise their answers.

Worker Population Ratios for Rural Women

DMAS Sample Ages 21-59

Note: The upper and lower bounds are the 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Author’s calculations based on DMAS data.

Worker Population Ratios for Urban Women

DMAS Sample Ages 21-59

Note: The upper and lower bounds are the 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Author’s calculations based on DMAS data.

Distribution of Activities Omitted in Status Listing for Urban and Rural Women

Source: Author’s calculations based on DMAS data.

Research Design Lessons

The fact that women’s work is under-enumerated is well recognized. However, the research community tends to advocate time use surveys in order to address this under-enumeration. Time use surveys are often expensive and difficult to carry out, particularly in low-literacy and rural settings where people may not keep track of time spent in various activities with the same level of precision as in urban settings.

The experiment reported here suggests that the use of a hybrid approach in which individuals are asked to identify their participation in activities most commonly undertaken in study settings may allow for greater capture of activities omitted by traditional labor force surveys.

These results also suggest the need for caution in interpretation of statistics on the decline in women’s work participation recorded by the NSS. While the questions themselves have not changed over time in these surveys, there has been an enormous change in the way in which the surveys have been conducted and the nature of investigators recruited for the surveys. In view of the increased reliance on contract investigators instead of regular staff, it is possible that the investigators do not fully understand what is meant by labor force participation and may carry their gender biases into the field. Thus, some of the recorded decline in women’s work participation in rural areas may be due to increased interviewer error. By clearly identifying the activities for which data is to be collected, the module incorporated in DMAS reduces the potential for interviewer error and bias.

References

Banerjee, N., and Jain, D. (1985). Tyranny of the Household: Investigative Essays on Women’s Work. New Delhi: Shakti Books.

NSSO (2019): Periodic Labour Force Survey, Annual Report, 2017-18. New Delhi: National Sample Survey Organisation, Government of India. Retrieved from http://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/Annual%20Report%2C%20PLFS%202017-18_31052019.pdf, Accessed 4 November 2020.

- Log in to post comments