DOES CULTURE MATTER OR FIRM? DEMAND FOR FEMALE LABOR IN THREE INDIAN CITIES

Maitreyi Bordia Das*, Manager in the Urban, Resilience and Land Global Practice of the World Bank

This paper is based on a unique survey of 618 firms, carried out in 2015, in three of the largest cities in the state of Madhya Pradesh (India) – Bhopal, Indore and Gwalior. Madhya Pradesh (MP) itself is emblematic of India’s Hindi speaking heartland and can be seen, in many ways, as representing north-Indian culture and norms. The paper fills a void in the policy literature, as it assesses the relative role of culture, as signified by attitudes of employers, and of firm characteristics, in hiring women. It is part of the World Bank’s dialogue with the Government of MP in higher education and the extent to which educational attainment leads to more jobs for women.

As in national-level analysis (World Bank, 2011), in MP too, women aspire to market work. When asked whether they would be willing to do paid work outside their homes, about 38 percent of working age women in urban MP sampled for the NSS (68th round) responded ‘yes’. Aspirations were higher among younger women: almost half the women under the age of 30 said they would like to work outside the home, with their aspirations for work having risen over time. Given the fact that about 20 percent of women in MP complete high school, and that half of all young women want to work outside the home, there is a clear disjuncture between women’s aspirations, their skills and their reality (World Bank, 2012).

This paper seeks to answer the question – what is the role of firm characteristics and attitudes of hiring managers in gender outcomes in hiring? It uses data from a unique survey of firms in Bhopal, Indore and Gwalior. The survey contains questions on the characteristics of firms, gender and skill profiles of workers and attitudes of hiring managers (who are often the owners) about female employees and what they expect of them.

Results

An important finding is that micro enterprises, firms that are engaged in manufacturing, those operating in Bhopal, compared to Indore or Gwalior, those with a broader geographical ambit and those with higher shares of temporary employees, are more likely to hire at least one woman. At the univariate level, service sector firms are more likely to hire women, but this advantage vanishes once women-owned firms are removed (for reasons of collinearity).

A second major finding is related to attitudes. The vast majority of employers espouse socially acceptable attitudes about women’s work and education, especially as there is no implication that these would affect their own families or firms. So, most agree that boys and girls should be equally educated, women should work after marriage and men and women should be equally compensated for equal work. At the multivariate level, employers who do not believe in wage equality are also less likely to have a female employee as are those who believe women should not work after marriage.

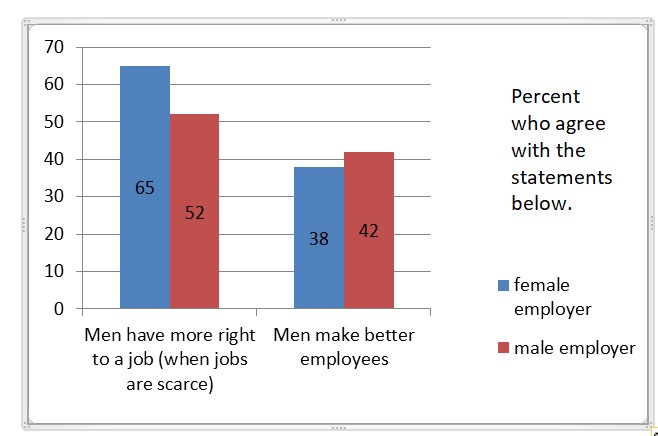

The variation across attitudes becomes much more inegalitarian when employers are questioned about the relative role of women and men as breadwinners, with over half saying that men have greater claim on jobs when jobs are scarce. There is similarly greater variation in the attitude that men make better employees than women do and that some jobs are better suited to men (or to women) (See Figure 1). The last attitude bears out in specific terms, where employers tend to reinforce the prevailing norms of occupational sex segregation.

Figure 1: Share of respondents who say that men have more right to a job and make better employees, by gender of respondent (n=618 employees)

Three additional findings that deserve reiteration and have implications for policy and action are:

1) Hiring process: Social networks matter much more than formal avenues of job search, especially for small and micro enterprises. This disadvantages more women compared to men, because the former have fewer networks, are less likely to move in circles where information about jobs is shared, and possibly less likely to be on electronic media. Women are also less likely to actively search for jobs in situations where they may have a starting disadvantage or may feel that they have a disadvantage.

2) Employee characteristics vary by occupation: Another finding is that the characteristics employers look for in male and female candidates vary by occupation. While most employers rate years of experience, job related skills and a right work ethic as the top qualities they would look for in a female employee, they rate a woman’s willingness to work long hours as the third most important quality – one that they do not consider as being important for men.

3) Lack of women focused policies: Finally, the data show that hardly any of the firms offer maternity leave or childcare. In fact, a little over one-fourth of the firms in the sample offered any benefits at all, and those that did, provided bonuses, incentives and/or food, and tended to be large and medium enterprises.

What are the implications of these findings and what can policy, associations of industry or lobbies that promote women’s employment do? It is likely that incentives such as transportation, childcare and paid maternity leave to women could improve the chances that more women would be employed, but small and micro firms may not be able to afford this and still stay profitable. Hence, there may be a case for fiscal or other incentives by government to firms to encourage hiring of women.

These results reinforce the conventional wisdom in some ways and are surprising in others. The most salient result is that employer attitudes matter much less for the chance that women will be hired, than do firm and location characteristics. The most important implication of these results is that they question an implicit assumption that culture is slow and hard to change and so, women will stay out of the labor market until social change occurs. This in turn has significant policy implications, the most important of which is that female employment in urban India is amenable to policy intervention and that there is no need to wait for culture to change.

References

World Bank. 2011. Poverty and Social Exclusion in India. World Bank: Washington D.C. 22

World Bank. 2012. Madhya Pradesh Higher Education Reform Options. South Asia Human Development Department. World Bank: Washington DC.

*Please see the full version of this paper written with co-authors Soumya Kapoor Mehta, Ieva Žumbytė, Sanjeev Sasmal and Sangeeta Goyal here.

- Log in to post comments