REPRODUCTIVE AND ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT: MEASUREMENT CHALLENGES AND DATA OBSTACLES

By Sarah Gammage, Yana van der Meulen Rodgers, and Shareen Joshi

Women across the world work daily to balance their dual roles as workers in the labor market and as the primary caretakers of children. In many contexts, skilled women who have access to formal sector jobs and high wages will postpone marriage and childbearing to accommodate work and caring. In other contexts, and in developing countries in particular, the pressures of combining childrearing with employment often relegate women to the informal sector, where they face insecure work arrangements and lack important safeguards for pay and working conditions.

The decision to work and to have children is generally mediated by access to reproductive health and care services, the availability of social protection, the type and quality of work available, and economic need. The “choice” of whether to work and the quality of work sought are likely to vary by women’s reproductive empowerment, which includes women’s ability to make decisions around fertility, express their sexual rights, and have access to a full range of reproductive health care services. For example, in Nigeria, women who reported more consistent contraceptive use had significantly higher odds of working as well as receiving cash payment (John et al. 2019). In the United States, Targeted Restrictions on Abortion Providers (TRAP) laws increased ‘job lock’ such that women living in states with TRAP laws are less likely to move between occupations and into higher-paying occupations (Mahoney et al. 2019). Moreover, in those countries where fertility transitions have been sharpest, fertility decline has not automatically translated into more employment and better labor market outcomes for women (Gammage et al. 2019). Investment in health care, education, labor market institutions and social protection has been critical in ensuring better labor market outcomes for women, illuminating a central role for coordinated policy.

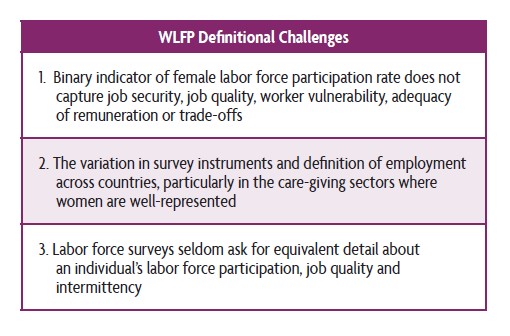

Understanding how to foster agency and choice in labor markets and in individual fertility through policy and programs requires better and more meaningful data. Much of the research on reproductive health, fertility, and employment remains constrained by data availability and data quality. One issue is that women’s labor market status is often measured by the female labor force participation rate, which is calculated from cross-sectional household surveys where the ILO definitions of labor force participation are employed to construct a binary indicator for employment. These definitions of labor force participation thus fail to capture labor conditions such as job security, job quality, worker vulnerability, adequacy of the remuneration, or more importantly, the trade-offs that women face.

A second issue is the variation in survey instruments and definition of employment across countries, particularly in the care-giving sectors where women are well-represented. The challenge of measuring this work leads to underreporting, undercounting and broad undervaluing of labor force participation and its role in the broader economy.

A second issue is the variation in survey instruments and definition of employment across countries, particularly in the care-giving sectors where women are well-represented. The challenge of measuring this work leads to underreporting, undercounting and broad undervaluing of labor force participation and its role in the broader economy.

A third issue is that while commonly used health surveys such as the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) frequently ask for detailed histories about fertility decisions and outcomes, labor force surveys seldom ask for equivalent detail about an individual’s labor force participation, job quality, and intermittency. Although the DHS has an excellent reputation for providing accurate data on a range of population and health topics (including reproductive health, family planning practices, household structures, and birth histories), the DHS has very blunt measures of women’s employment status and no information on their job tenure, employment histories, or working conditions.

Images of Empowerment

Beyond these definitional challenges for measuring women’s employment status, there are methodological challenges. One of the key methodological hurdles is presented by the endogeneity of the decision of whether or not to work, and the decision to bear children. That is, women’s fertility may be determined jointly with their employment status, so in a typical linear regression of women’s fertility determinants, an independent variable measuring their employment could be correlated with the regression’s error term. Many researchers have tried using an instrumental variables strategy or a two-stage procedure can help to address endogeneity bias. Unfortunately, a common problem is finding valid instruments that have strong predictive power in explaining the suspected endogenous independent variable without also serving as determinants of the dependent variable (in this case, women’s fertility). In other words, the challenge is to find at least one exogenous variable that can explain women’s employment status without having a direct effect on fertility.

Facing such challenges, we need to think about broader research methods and develop new conceptual frameworks that address not only the simultaneity of employment decisions and fertility outcomes, but also the importance of their co-evolution. Listening to women and women’s movements and asking women about their needs and choices, and combining qualitative and quantitative data, will be key to improving wellbeing of mothers, families and children. This is not merely an empirical conundrum. To make this analysis devoid of rights bypasses the most critical feature of the analysis and its centrality for human wellbeing, which is to surface agency and facilitate choice.

Without a doubt, resolving care needs is integral to this approach. Women’s widespread retreat from the labor market across the globe as a result of COVID19 only underscores this point. The mediating factor that facilitates women’s employment, particularly for women with children and those caring for the elderly and the sick, is the provision of care services. The right to care and be cared for should be a foundational principle guiding our understanding of how societies address care needs and care deficits (Power, 2004). Moreover, the quality of care is intrinsically linked to the right to care and be cared for. Integrating reproductive rights into our analysis is essential for surfacing viable solutions to the challenges women encounter in the labor market and in realizing their fertility preferences.

Please see our full article here.

![]()

- Gammage, Sarah, Naziha Sultana, and Allie Glinski. 2019. “Reducing Vulnerable Employment: Is there a Role for Reproductive Health, Social Protection and Labor Market Policy?” Feminist Economics 26: 121-153.

- John, Neetu, Amy Tsui, and Meselech Roro. 2019. “Quality of Contraceptive Use and Women’s Work and Earnings in Peri-Urban Ethiopia,” Feminist Economics 26: 23-43

- Mahoney, Melissa, Kate Bahn, Adriana Kugler, and Annie McGrew. 2019. “Do TRAP Laws Trap Women into Bad Jobs?” Feminist Economics 26: 44-97

- Power, Marilyn 2004. “Social Provisioning as a Starting Point for Feminist Economics,” Feminist Economics, 10:3, 3-19.

- Radhakrishnan, Uma. 2010. A Dynamic Structural Model of Contraceptive Use and Employment Sector Choice for Women in Indonesia (Paper No. CES-WP-10-28). Retrieved from U.S. Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies: http://www2.census.gov/ces/wp/2010/CES-WP-10-28.pdf.

- Log in to post comments