SEXUAL MATURITY LAWS IN INDIA: GIRLS’ DISTINCT INTERESTS

By Ashwini Tambe

Legal age standards for sexual maturity have become a flashpoint in India over the past decade. After a century of tireless advocacy to raise the legal age of sexual consent and age of marriage, some feminists are arguing to lower both. What we’re witnessing is a very belated identification of girls’ distinct need for freedom from parental control. The boundary between girls’ issues and women’s issues in feminist politics has long been porous: historically, women have advocated for girls in a maternalist register, such as in campaigns against sexual slavery. But there is a clear fissure between maternalist women’s advocates who claim to protect children but speak in the voice of parents, and those feminists who are critical of laws that increase parental sexual control. This latter perspective, which I advance in my book Defining Girlhood in India: A Transnational History of Sexual Maturity Laws (University of Illinois Press 2019), is especially urgent given how parental control over girls frequently perpetuates caste and religious endogamy. The question I explore is, what would it mean to not imagine girls’ issues as a subset of women’s issues but rather as being in tension with them?

The fissures between women’s issues and girls’ issues in India have come to a head in the past decade primarily because of the passage of new laws specifying the age boundaries of sexual maturity: the 2012 Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO Act) and the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 2013. In May 2012, child-welfare advocates, led by the Ministry of Child and Welfare Development, pushed for the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO Act). This law set punishments for a range of sexual offenses involving children, from assault and harassment to viewing pornography with a child. It was the first law in India specifically focused on child victims, including male victims, and primarily imagined adult perpetrators. Its most significant feature was defining anyone under 18 as a child and setting 18 years as the standard age of sexual consent.

Defining Girlhood in India: A Transnational

History of Sexual Maturity Laws

This new age of sexual consent has implications for how cases of consensual teenage sexual activity are understood. All sex in the age range of 16-18 can now be deemed criminal. As Amrita Pitre and Lakshmi Lingam (2021) observe, citing studies conducted in Delhi, Lucknow, and Mumbai, a large number of the cases filed under this law are an outcome of parents’ unhappiness about their adolescent children’s consensual sexual activity.1 Pitre and Lingam argue that this environment of attempted control over adolescent sexual practices makes it difficult for adolescents to access sexual and reproductive healthcare they need. As a 2021 Center for Reproductive Rights study study by Chandra et. al. explains, the POCSO Act’s mandatory reporting obliges doctors to report cases of underage sexual relationships to the police, seriously affecting the provision of sexual and reproductive healthcare to teens.2 The requirement has been especially damaging for pregnant teens under 18 in consensual relationships who cannot find avenues for safe legal abortions. The report details cases from Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and Jharkhand of teen pregnancies resulting in a host of negative consequences: clandestine abortions and even forced marriages to alleviate the stigma of children born out of wedlock.3 Although the POCSO Act’s introduction of mandatory reporting was intended to address the underreporting of child abuse, it has led to “denial or delay in accessing safe abortions” (p.140) and is a deterrent to sexually active young people below 18 seeking reproductive and contraceptive services from accredited medical professionals.4 In a 2016 National Law School of India University study of the POCSO Act in Delhi, nearly 30% of the cases involved a prior romantic relationship --either as a boyfriend or someone who was married subsequently (p.64).5 Over 96% of such cases resulted in an acquittal because of the purported victim’s refusal to testify against a sexual partner, and in 99% of cases where the accused subsequently married the victims, the courts acquitted the accused (p.65). This report also notes the pressure on adolescents to resort to marriage. The report notes that an “unintended consequence of the criminalization of all forms of sexual contact with a child under POCSO Act appears to be a spike in the number of child marriages.” (p.24.)

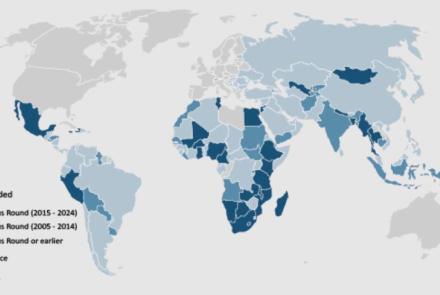

While the POCSO Act focused specifically on a spectrum of abuses that children experience, laws pertaining specifically to sexual assault have also hardened 18 as a sexual age standard. The Criminal Law Amendment Act, passed in April 2013, further consolidates the age provision of the POCSO Act. This law, passed speedily in the aftermath of the horrific murder and gang rape of Jyoti Singh Pande in Delhi in late 2012, aimed to expand protective measures; it increased the age of statutory rape to 18. Feminist groups protested this new age-related feature when the bill was discussed, but quite predictably, several legislators seized the opportunity to characterize this debate as a battle about Indian values, casting feminists as being “anti-Indian.” With the passage of the CLMA, India is now has one of the highest age of sexual consent in the world. Again, this enshrining of 18 as the age of sexual consent enables parents to frame consensual sexual relationships as crimes.

The third arena in which parental control has expanded is in laws directly pertaining to child marriage. The minimum age of marriage for girls in India is currently 18 years- it was raised to 18 in 1978, and the 2006 Prevention of Child Marriage Act (PCMA) put in motion measures that enabled its easier enforcement, primarily by rendering early marriages potentially voidable. The law is intended to prosecute parents who arrange the marriages of their children too early. However, it has also been frequently used by parents who wish to prevent marriages their children undertake against their wishes. Parents have widely mobilized PCMA measures to protest elopements by declaring “void” the marriages that they refuse to accept—and most often these are marriages that are inter-caste or inter-religion. Flavia Agnes, who heads the Mumbai-based Forum against Oppression of Women, notes that the law against child marriage has frequently become “a weapon to control the expression of sexuality, and curb voluntary marriages, and is used to augment parental power.” Agnes represents a segment of feminist activists who raise strong cautions about patriarchal practices perpetuated in the name of protection. Agnes has also strenuously argued against the CLAA’s raising of the age of statutory rape from 16 to 18 and has led the charge, shared by other women’s groups, that raising this age of consent, in fact, curtails, rather than extends, young women’s freedoms. This position is distinct from state-affiliated women’s bodies, such as the National Commission on Women that regularly presents itself in a protective maternalist voice as upholding children’s (and especially girls’) interests, but promotes policies that advance parental control.

There are distinct stakes that parents have with respect to sexual maturity laws in India. Whether we are discussing cases under POCSO (child abuse), CLAA (rape), or PCMA (marriage), what prosecuting parents most often seek to preserve is their right to shape their child’s marital choice. Parents’ reasons for arranging early marriage are varied across class and caste. Poverty propels some Hindu parents to arrange marriages early in hopes of having to pay lower dowries. In other cases, low-caste parents’ fear for their daughter’s safety in environments of great physical insecurity drives early marriage. For members of minority religious communities, a need to continue lineage against the drive to assimilate pushes parents to secure matches early. For high-status families, ensuring the orderly transmission of property is the key reason for arranging early marriage.

Parents routinely justify arranged marriages in paternalistic terms: that close ties between natal and conjugal families prevent a daughter from feeling alienated in a new family, or that parental supervision of mate selection protects their daughters from predatorial or deceptive strangers. In a caste-and religion-riven society, however, arranged marriages are primarily a lynchpin in preserving the existing social order. Sustaining caste and religious identities is the most important consequence of parents arranging marriages. The question is, should laws intended to prevent the sexual abuse and assault of children become instruments of this agenda? Feminist groups underscore that the current age of sexual consent now unduly empowers parents. It is time to seriously debate whether raising the age of sexual consent to 18 years and the implementation of the PCMA have actually served the interest of girls.

1 Pitre, Amrita & Lingam, Lakshmi (2021). Age of consent: challenges and contradictions of sexual violence laws in India. Sexual and reproductive health matters, 29(2), 1878656. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2021.1878656

2 Aparna Chandra, Mrinal Satish, Shreya Shree, Mini Saxena and the Center for Reproductive Rights (2021) “Legal Barriers to Accessing Safe Abortion Services in India: A Fact Finding Study.” Bengaluru: National Law School of India University. https://reproductiverights.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Legal-Barriers-to-Accessing-Safe-Abortion-Services-in-India_Final-for-upload.pdf

3 Ibid., p.140-144

4 Ibid., p. 140

5 Center for Child and the Law, 2016 “Report of the Study of the working of Special Courts under the POCSO Act 2012, in Delhi.” Bengaluru: National Law School of India University. https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/review?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:29a3e2d8-11f0-4e55-9c6a-98a9840f8a35#pageNum=1

- Log in to post comments