WEDGE EMERGE Seminar: Counting Women's Paid Work

Summary by Amy McLaughlin

WEDGE/EMERGE Collaborative Seminar Interrogating Gender Data

Feminist activists and researchers continue to struggle with the challenge of meas uring women’s economic activities. Micro studies consistently document that women’s economic activities in developing countries are significantly undercounted. Why is it that even after decades of advocacy, statistical systems continue to undercount women’s work? Is it worthwhile continuing to lobby for better measurement? These are the questions, Renana Jhabvala of the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), Bharat and co-founder and board chair of WIEGO, addressed in a web based discussion on January 22, 2021.

uring women’s economic activities. Micro studies consistently document that women’s economic activities in developing countries are significantly undercounted. Why is it that even after decades of advocacy, statistical systems continue to undercount women’s work? Is it worthwhile continuing to lobby for better measurement? These are the questions, Renana Jhabvala of the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), Bharat and co-founder and board chair of WIEGO, addressed in a web based discussion on January 22, 2021.

The WEDGE program from the University of Maryland, and the EMERGE program from UC San Diego, jointly hosted a discussion entitled, “Interrogating Gender Data: Conversations about Measurement,” that focused on evaluating measures of women’s paid economic activities and generating ideas for their refinement. Renana Jhabvala started this discussion by showing that women’s economic activities continue to be undercounted in spite of decades of research noting this discrepancy (for a comprehensive review of micro studies, see Mehta, 2018). One of the main causes for this may be the prevailing social norm that men are and should be the primary breadwinner for a family; this norm continues to shape the perception of what is counted as work and what is not. Women often do not report themselves to be workers, and additionally many surveyors do not probe properly to ascertain that the women are in fact engaged in money-generating activities.

Using examples of her work at SEWA, Renana Jhabvala noted that undercounting women’s contribution prevents advocates from being able to secure buy-in from legislators who might be involved in crafting policy to support women working. SEWA is often asked about official numbers of women working in a particular field, for example, as street vendors. Official counts rely on NSS data that have undercounted the women in that field and so when SEWA works to reserve spaces for female street vendors, not enough spaces can be reserved. In addition, new labour codes allocate funds for home based workers but undercounting means SEWA is not able to bring these benefits to women. This undercounting includes women who work as domestic workers, construction workers, farmers, and livestock producers.

Throughout its existence for the last 40 years, SEWA has had some policy victories, including:

- Bringing the informal sector to the attention of researchers and policy makers

- Influencing survey designs to include specifying a place of work

- Adding a module on informal workers in employment/unemployment surveys

- SEWA has sponsored its own surveys to provide alternate counts (e.g. Sharit Bhoumik’s 2010 work on street vendors.

The importance of precise data on women’s work cannot be underestimated; statistics are a weapon that must be accurate in order to improve women’s lives.

Three expert commentators, Kunal Sen, Kathleen Beegle, and Yana Rodgers reacted to Jhabvala’s comments by noting the discrepancies in measurement of women’s work across different regions, identifying some of the causes of these discrepancies and suggesting broadening the aspects of women’s work that are measured.

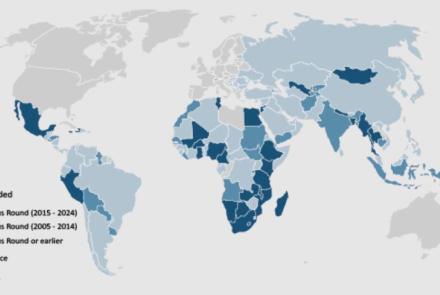

Kunal Sen, Director of UNU-Wider and Professor of Economics at the University of Manchester, used country level data to show disparities across surveys and to explore the reasons behind this undercounting. He urged researchers to make better use of existing data by being aware of its inherent flaws.

Kathleen Beegle, Lead Economist with the World Bank Gender Group, suggested that the undercounting of women’s work can be attributed to a variety of causes, including:

- Sampling households incorrectly

- Determining who is a regular household member from the roster. Servants or workers may be not counted.

- Counting migrant workers inconsistently.

- Challenges in proxy reporting where male respondents may undercount (and under value) women and children’s work.

- Questionnaire design flows that can be addressed via probes and follow-up questions to draw out women’s work even if they themselves don’t define it as such.

- Coverage and content of questions may not always be well designed to capture casual work.

She concluded with the challenge of comparing estimates of women’s work across surveys and noted that without taking into consideration different ways of defining work, varied recall periods, handling of unpaid work from family members, troublesome definitions of self-employment and microenterprises, and irregularities counting casual labor, it will be difficult to obtain comparable data.

In conclusion, Yana Rodgers, Director of the Center for Women and Work at Rutgers University, advocated expanding the aspects of women’s work that are measured in labor force surveys. She argued job quality is an issue that needs a great deal more elaboration in standard surveys with focus on:

- differences between the formal and informal sectors

- job security

- adequate pay

- job vulnerability

- job conditions

- nature of the work itself

- labor market intermittency

- more longitudinal data

A lively discussion followed the formal presentations that further refined and elaborated on the important points above.

A recording of the event is available here.

Future discussions will explore measurement of norms regarding women’s economic empowerment and measurement of unpaid work. Please contact wedgeprogram@gmail.com if you would like to participate in future discussions.

- Log in to post comments