WHY WE SHOULD MEASURE SONLESS FAMILIES

By Keera Allendorf

Sex ratios—typically the number of males per 100 females—measure the sex composition of populations. Commonly used sex ratios cover entire populations, as well as specific age groups and births. Sex ratios also measure gender inequalities. High juvenile sex ratios, for instance, indicate young girls experienced mortality at higher rates than boys. Similarly, elevated sex ratios at birth signal parents aborted female fetuses at higher rates than male fetuses.

While sex ratios are versatile and valuable, we should add another measure of sex composition to our toolkit—the share of families that are sonless, specifically, the percentage of mothers aged 40-49 years with only daughters. In the numerator of this quantity are mothers who have only daughters, while mothers of only daughters, only sons, and a mix of both are placed in the denominator. This quantity is easily calculated using readily available data. Many surveys, including Demographic and Health Surveys, routinely ask women up to the age of 49 years about the number and sex of their children. Women aged 40-49 years with at least one living child can proxy families in which childbearing is largely complete.

Measuring sonless families emphasizes sex composition within families. A family-oriented measure is valuable for three reasons. First, people influence, and perhaps understand, sex composition through a family perspective. It is families pursuing and preferring sons that imbalances sex ratios. In patrilineal contexts, which are home to much of the world’s population, sons continue family lineages, inherit wealth, and hold great cultural significance. Families ensure sons by stopping childbearing only when they have a boy or by using sex-selective abortion to abort unwanted female fetuses. Further, the sex composition of one’s family—only daughters, only sons, or mixed—is likely an important way in which sex composition is understood in everyday life.

Second, substantial numbers of sonless families may benefit women and girls. Sonless families may treat daughters more like customary sons. For instance, parents may invest in daughters’ careers, bequeath wealth to daughters, co-reside with daughters, and rely on daughters for old age support. Sonless families may also go outside the family entirely for meeting some needs. Instead of relying on children for old age support, for example, they may rely on their own savings, government assistance, and paid caretakers. I found that women in India adjusted expectations of old age support in precisely this way (Allendorf 2020). Mothers of sons kept or further embraced patriarchal expectations of a son providing old age support, while sonless mothers gave up patriarchal expectations and turned to daughters or other sources for such support. When sonless families are rare, such adjustments may be inconsequential. If sizable shares of families are sonless, however, their adjustments may spur normative and institutional changes that eventually weaken patrilineal family systems.

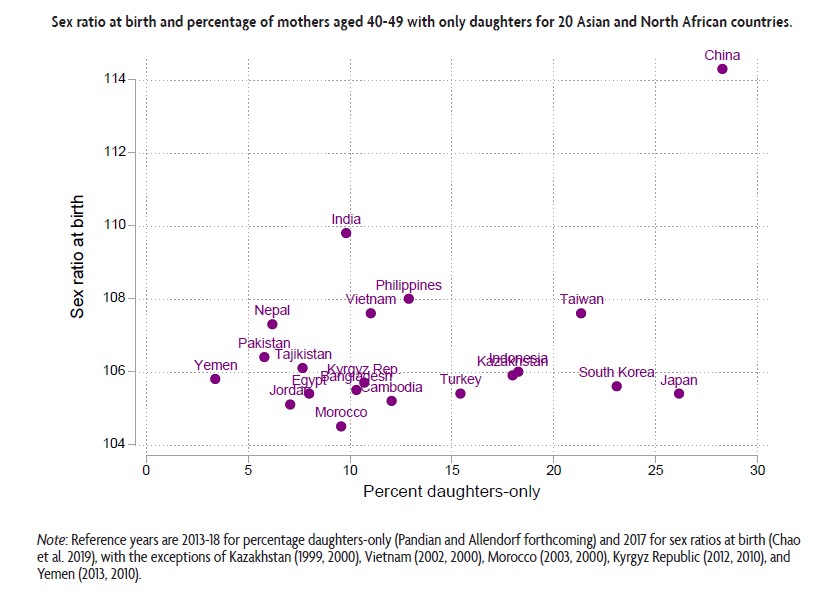

Third, sonless families and sex ratios provide distinct views of sex composition. The two population behemoths—China and India—illustrate how these measures are complements, rather than substitutes. China and India are (in)famous for their imbalanced sex ratios. While a normal sex ratio at birth is around 105 males per 100 females, China has the highest sex ratio at birth in the world at 114 and India is not too far behind at 110 (Chao et al. 2019). Yet, their levels of daughters-only families differ markedly. China has an astonishingly high share of sonless families at 28 percent, while 10 percent of Indian families have only daughters (Pandian and Allendorf Forthcoming). China has lost many millions of girls to sex-selective abortion, yet simultaneously, large numbers of sonless families are abandoning patrilineal filial piety and financial exchanges. In India, by contrast, a skewed sex ratio at birth is paired with a moderate level of sonless families. As seen in the scatterplot for 20 Asian and North African countries, India’s percentage of daughters-only families is roughly in the middle of the pack.

In closing, I want to highlight the importance of fertility for both measures of sex composition. When fertility is high and families have large numbers of children, a son is nearly guaranteed. When fertility declines and families have few children, the probability of having a son drops. It is when fertility is low that many parents in patrilineal contexts continue childbearing until they have a boy or use sex-selective abortion. A large and rich collection of research shows how these dynamics skew sex ratios and harm women and girls. At the same time, however, other families are unwilling, unable, or unsuccessful in securing sons. Sonless families are rising as fertility declines in many Asian countries (Pandian and Allendorf Forthcoming). Research measuring sonless families and assessing the potential benefits for girls and women is now needed.

![]()

- Allendorf, Keera. 2020. “Another Gendered Demographic Dividend: Adjusting to a Future without Sons.” Population and Development Review 46(3): 471-499.

- Chao, Fengqing, Patrick Gerland, Alex R. Cook, and Leontine Alkema. 2019. “Systematic Assessment of the Sex Ratio at Birth for All Countries and Estimation of National Imbalances and Regional Reference Levels.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(19): 9303-9311.

- Pandian, Roshan K. and Keera Allendorf. Forthcoming. “The Rise of Sonless Families in Asia and North Africa.” Demography.

- Log in to post comments