GENDER AND EMPLOYMENT IN A TIME OF PANDEMIC IN INDIA

By Sonalde Desai, Neerad Deshmukh and Santanu Pramanik

Because of the very recent occurrence of the COVID-19 crisis and the paucity of empirical evidence, we are forced to look at prior financial crises for insights on gender differences in employment during crises. Here the evidence is mixed. The Asian economic crisis of 1997 resulted in a greater decline in women’s employment in South Korea. However, in Indonesia, women increased their work hours to make up for male unemployment (Aslanbeigui and Summerfield 2000). The Great Recession of 2008 led to greater declines in male employment as compared to female employment, though there is some evidence that the level of unemployment for some groups of women was much higher than the corresponding aggregate figures for men (Fukuda-Parr, Heintz, and Seguino 2013). Most important, the impact of the financial crisis was mediated by the differential concentration of men and women in different occupations and industries.

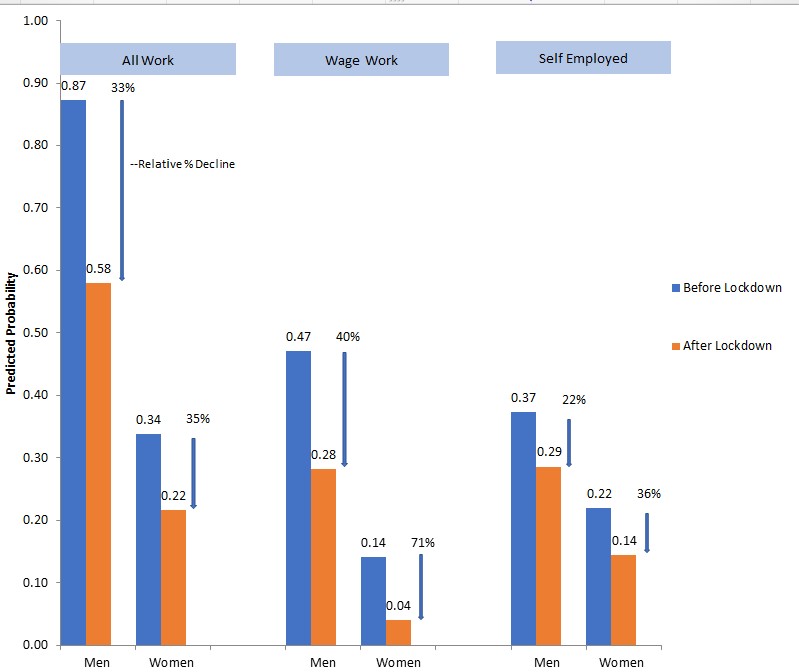

Desai, Deshmukh and Pramanik, in a paper forthcoming in Feminist Economics compare women’s and men’s employment in Delhi National Capital Region using data from monthly telephone interviews initiated in March 2019. In response to the pandemic, Indian Government announced a lockdown on March 24, 2020 which was gradually relaxed after June 1, 2020. The results from individual-level random-effects models show that contrary to prior expectations, though both men and women experienced a decline in employment during the lockdown, the impact was greater for men than for women.

This finding is primarily because men and women tend to work in different sectors; men are more likely to participate in wage work, while women are mainly concentrated in self-employment. Before the lockdown, 58 percent of male workers in the sample area were employed in wage work, while only 36 percent of the female workers were employed as daily or monthly wage workers. Since the lockdown had a greater impact on wage work than on self-employment, women were somewhat protected from its negative impacts. However, when analysis focused only on wage work, the study found that women wage workers have a greater likelihood of being out of work than their male counterparts. Predicted probabilities of employment before and after lockdown for men and women from random effects models holding all other variables at their mean value are presented in Figure 1.

These results highlight the importance of accurately measuring participation in wage as well as self-employment. As the WEDGE Measurement Memo of November 2020 highlighted, capturing women’s self-employment in agriculture and micro businesses requires research design that takes into account devaluation of women’s non-wage activities by both interviewers and respondents. If sufficient attention is not paid, women’s employment data will underestimate self-employment and consequently, impact of pandemic will focus largely on wage employment and overestimate gender differences in employment. It also suggests that the recommendation of 19th International Conference of Labor Statisticians, now adopted by International Labor Organization, that excludes employment for subsistence production, may not allow us to fully appreciate the role of agriculture in providing risk insurance during the pandemic.

Figure 1: Predicted Probability of being employed in different types of work before and during lockdown for men and women (Target population: Delhi National Capital Region)

References

Aslanbeigui, Nahid and Gale Summerfield. 2000. “The Asian Crisis, Gender, and the International Financial Architecture.” Feminist Economics, 6 (3): 81-103.

Fukuda-Parr, Sakiko, James Heintz, and Stephanie Seguino. 2013. “Critical Perspectives on Financial and Economic Crises: Heterodox Macroeconomics Meets Feminist Economics.” Feminist Economics 19 (3): 4-31.

- Log in to post comments