Land Ownership and Access Among Indigenous and Rural Mapuche Women

By Constanza Hurtado

Project Overview

Motivation

- Latin America is one of the regions with the largest share of women in agriculture.

- Scarce information regarding land ownership that have radically change in the last decades due to changes in laws and increasing private companies in Latin American agriculture

- Land ownership and rights could be more important for women empowerment than female labor participation (Arawal, 1994)

- Land ownership is related to lower domestic violence among young girls

- Land ownership is a source of empowerment

- Feminization of agriculture (industrialization and exportation increased in the last 30 years)

Context: Mapuche Lands in Chile

- Mapuche are the bigger indigenous Chilean population (8% at national level and 18% at rural areas). They are concentrated on the Metropolitana and Araucania regions.

- As other Latin American indigenous population, Mapuche have growth in the last decades

- Indigenous in Chile are younger, poorer (15 vs 8%), and have lower education (especially those living in rural areas) in comparison to non-indigenous Chilean population

- Indigenous in Chile are similar in female employment (44%), female head of HH (44%), informal employment, and house ownership (20% of Mapuche live in inheritance houses), in comparison to non-indigenous Chilean population

- Indigenous highlight for high participation in social/political organizations, especially in rural areas and women. There are 3000 Mapuche communities in the La Araucania.

- Although they have their language (Mapuzungun) two thirds of Mapuche do not speak it; hence, almost all alive Mapuche speak Spanish

- Land property (Jaimovich, 2019)

- Until 1860 land distribution on the region based on indigenous rules.

- Between 1880 and 1929, land property organizational trough titles (títulos de Merced) (500,000 ha.). Nonetheless, some of these lands were taken from Mapuche.

- Between 1962 and 1973, National Agrarian Reform (150.000 ha. gave to Mapuche), but the Military goverment (1973-1990) took these lands from the indigenous population.

- Since 1990 Mapuche communities have struggled to recover their properties. The government created a policy (1994) to recover some of these lands (200,000 ha.) and give to families or communities.

- Chilean agriculture depends on the private sector, and small peasants sell their products to big companies (Deere, 2014). Rural Mapuche participate in this economy but also sell products to other Mapuche communities.

- Mapuche worldview centralizes place and land. The word Mapuche means “people from the land”; they commercialized their own products (e.g. piñones) (Richards, 2003)

Gender

- The discourse of the difference (the right to a different treatment, because of women uniqueness) has been crucial on the rights struggle of indigenous women in Latin America (Richards, 2003; 2006)

- Mapuche women highlight for their political leadership in political/territorial conflicts; and lack of relevance on traditional gender struggles toward more equality (Richards, 2003)

- Gender is dual and complimentary on their religion and worldview, and Mapuche women differ in their views about patriarchy and machismo. Hence the sense of community and their struggles is more salient than traditional claims toward more equality. However there are differences by generations (Richards, 2003)

Gap

- There are no national statistics regarding land ownership by gender in Chilean rural areas. Knowing the year, and method of acquisition of lands (inheritance rules vs. other mechanisms), and its relationship with other events (e.g., marital story) is crucial to advance on the knowledge of the female status in Latin America.

- Because of recent changes in land rights rules and gender norms, knowing if there are differences between generations on access to land ownership for women, it is crucial to understand how laws and privatization of agriculture in Latin America interact with women empowerment.

- Mapuche gender ideology is in tension with non-indigenous gender ideologies. Disentangling Mapuche female access to land property traditions could shed light on the interaction between these ideologies

Proposal

- Develop a survey module about access to land among Mapuche women.

- 5 to 8 interviews with young (15 to 45) and older women (older than 60) from the Mapuche community to understand their worldvision about women's access to land.

- 15 to 25 surveys with women from different generations (contacted trough a friend and snowball with the Mapuche community)

- Topics:

- Land ownership at the household level

- Acquisition method

- Use of the land

- Access to land ownership for women

- Changes over time

- Traditions regarding land property

- Land legal status

- Family relations and land ownership

- Land ownership and homeownership

Plan

- Phase 1: Research

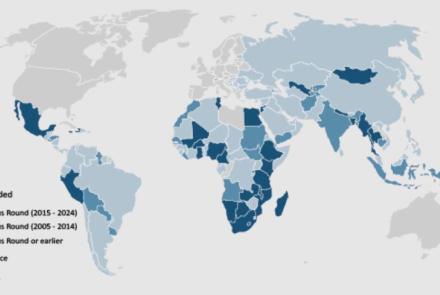

- Activities: Literature Review, Questionnaires Review at the international level, Talking with experts (e.g., Chilean Anthropologists, WEDGE professors), Data analysis, and UMD IRB approval.

- Phase 2: Questionnaire design

- Activities: Design questions (for the interview, and survey), Share with experts for comments, the final version of the questionnaire.

- Phase 3: Fieldwork

- Activities: Planning the visit to the community, Contacting interviewees, conduct interviews, and surveys (1 hour each one).

- Phase 4: Analysis

- Activities: Analyzing responses (i.e., topics, phrasing and wording, comprehensibility, new questions).

- Phase 5: Final report

- Activities: Synthesize results, sharing with WEDGE professors, comments and reviews, and conclusions for similar modules at Latin American level.

Selected bibliography

- Agarwal, B., & Bina, A. (1994). A field of one's own: Gender and land rights in South Asia (Vol. 58). Cambridge University Press.

- Allendorf, K. (2007). Do women’s land rights promote empowerment and child health in Nepal?. World development, 35(11), 1975-1988.

- Carter, M. R., & Barrett, C. B. (2006). The economics of poverty traps and persistent poverty: An asset-based approach. The Journal of Development Studies, 42(2), 178-199.

- Deere, C. D. (1990). Household and class relations: peasants and landlords in northern Peru. Univ of California Press.

- Deere, C. D. (2009). The Feminization of Agriculture?: The Impact of Economic Restructuring in Rural Latin America. In The Gendered Impacts of Liberalization (pp. 115-144). Routledge.

- Deere, C. D., & De Leal, M. L. (2014). Empowering women: Land and property rights in Latin America. University of Pittsburgh Pre.

- Diana Deere, C., Alvarado, G. E., & Twyman, J. (2012). Gender inequality in asset ownership in Latin America: Female owners vs household heads. Development and Change, 43(2), 505-530.

- Jaimovich,D. (2019). Las tierras mapuche a través de la historia. Documento de trabaj 4001. Mapuche Data Project.

- Richards, P. (2003). Expanding women's citizenship? Mapuche women and Chile's national women's service. Latin American Perspectives, 30(2), 249-273.

- Richards, P. (2006). The Politics of Difference and Women’s Rights: Lessons from Pobladoras and Mapuche Women in Chile, Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, Volume 13, Issue 1, Spring 2006, Pages 1– 29, https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxj003

Photo by Juan Arredondo on Images of Empowerment