RETHINKING THE GENDER DIVISION OF HOUSEHOLD LABOR DURING WUHAN’S CORONAVIRUS LOCKDOWN

By Yue Qian, University of British Columbia

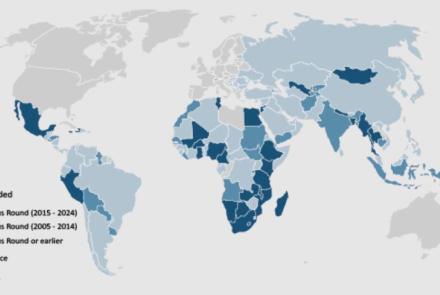

The COVID-19 pandemic and its associated mitigation policies have upended the way we live and work. Many countries in the world have implemented lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, or shelter-in-place mandates. Wuhan, a Chinese city of 11 million people and the original epicenter of the pandemic, was placed under the world’s first COVID-19 lockdown. During Wuhan’s lockdown, planes and trains leaving Wuhan were canceled, public transportation within the city was suspended, the use of private cars was banned, and, for a long time, residents could not leave their residential compounds without authorization (Qian & Hanser 2021). This strict lockdown lasted 76 days, spanning from January 23 to April 8 of 2020.

How did Wuhan residents cope with the 76-day lockdown? My research team, with funding support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, conducted in-depth interviews with nearly 80 residents of Wuhan and collected detailed accounts of how they lived through this unprecedented lockdown. While researching the experiences of Wuhan residents, I was also investigating the impact of the pandemic on men’s and women’s employment in North America. In both Canada and the United States, the employment of mothers with young children dropped more than that of fathers during the pandemic (Qian & Fuller 2020; Yavorsky, Qian, & Sargent 2021). The disproportionate decline in maternal employment during COVID-19 was due in part to the closures of schools and childcare facilities (Collins et al. 2021; Fuller & Qian 2021). These patterns also occurred in other countries (Alon et al. 2021).

Most discussions about gender, employment, and household labor during the pandemic have focused on the role of formal childcare infrastructure and the division of physical tasks among different-sex couples (e.g., cooking, cleaning, homeschooling children) (for a review, see Yavorsky, Qian, & Sargent 2021). My research on Wuhan, however, draws attention to the role of informal childcare supports in Chinese families and the increased demands of cognitive labor during lockdowns. Below, I use one participant from my Wuhan research to illustrate this point.

Tang Jing (pseudonym), a 36-year-old woman, worked for a private company and lived with her 4-year-old daughter, her husband, and her mother. During Wuhan’s lockdown, she and her husband quickly transitioned to teleworking. Similar to US workers, workers in China faced continued pressures to work long hours during the pandemic. She said, “my boss may also hold online meetings on Saturdays and Sundays to assign work. Since we were at home anyways, there was no difference between workdays and weekends. We were always on call.”

How did she manage to keep her job and work long hours while having a preschooler at home? Compared to US parents, many Chinese parents live with the grandparent generation, which helps to maintain the employment of mothers with young children (Tan, Ruppanner, & Wang 2021). Intergenerational coresidence and “selfless intensive grandmothering” (Ji et al. 2020: p.133), both of which were already common in China before the pandemic, were reported by many of my research participants from Wuhan. As Tang Jing noted: “Even before the pandemic, Grandma attended more to my daughter’s everyday needs. It was also the case during the pandemic. Grandma did more of the work such as playing with her or babysitting her.”

Even with the help of grandparents, women may still do more cognitive labor, especially given the pandemic circumstances. In a recent article published in the American Sociological Review, Allison Daminger (2019: p.609) shows that “cognitive labor entails anticipating needs, identifying options for filling them, making decisions, and monitoring progress.” Daminger (2019) further reveals that cognitive labor is gendered: Overall, women bear a larger share of cognitive labor than their husbands do, and the most invisible, underappreciated cognitive tasks—anticipation and monitoring—are disproportionately led and completed by women.

The demanding nature of cognitive labor and the gendered distribution of this oftentimes invisible labor were vividly illuminated in Tang Jing’s accounts. Tang Jing told us:

“It wasn’t easy to buy groceries during the lockdown. Each time, we had to buy as many groceries as possible. I worried about that, every morning when I woke up, things like where to buy groceries? what to eat today? what was still left in the fridge? My husband cooked, but he did not worry about buying groceries, maybe because he knew that I would do it.”

Although Tang Jing perhaps did not even realize it, it clearly was mentally-taxing and time-consuming to recognize upcoming family needs, find out potential solutions, decide what to do, and monitor the entire process. The uncertainty, resource scarcity, and threat of COVID-19 infections only made it extra challenging to accomplish the cognitive labor required.

In many countries, the pandemic has disrupted people’s daily routines. Tang Jing’s experiences suggest that, in addition to examining how couples divided physical tasks, it is fruitful to consider how cognitive labor (such as planning and managing family needs) shaped gender inequality in family and work during COVID-19. Also, the presence of grandparents could provide a family safety net for working mothers, but women likely face the double burden of childcare and elderly care if grandparents are sick. The lived experiences of Wuhan residents highlight the importance of considering informal care provision, intergenerational support, and cognitive labor in work-family and COVID-19 research.

![]()

- Alon, T., Coskun, S., Doepke, M., Koll, D., & Tertilt, M. (2021). From Mancession to Shecession: Women’s Employment in Regular and Pandemic Recessions (No. w28632). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Collins, C., Ruppanner, L., Christin Landivar, L., & Scarborough, W. J. (2021). The Gendered Consequences of a Weak Infrastructure of Care: School Reopening Plans and Parents’ Employment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gender & Society, 35(2), 180-193.

- Daminger, A. (2019). The cognitive dimension of household labor. American Sociological Review, 84(4), 609-633.

- Fuller, S., & Qian, Y. (2021). Covid-19 and The Gender Gap in Employment Among Parents of Young Children in Canada. Gender & Society, 35(2), 206-217.

- Ji, Y., Wang, H., Liu, Y., Xu, R., & Zheng, Z. (2020). Young women’s fertility intentions and the emerging bilateral family system under China’s two-child family planning policy. China Review, 20(2), 113-142.

- Qian, Y., & Fuller, S. (2020). COVID-19 and the gender employment gap among parents of young children. Canadian Public Policy, 46(S2), S89-S101.

- Qian, Y., & Hanser, A. (2021). How did Wuhan residents cope with a 76-day lockdown?. Chinese Sociological Review, 53(1), 55-86.

- Tan, X., Ruppanner, L., & Wang, M. (2021). Gendered housework under China’s privatization: the evolving role of parents. Chinese Sociological Review, 1-25.

- Yavorsky, J. E., Qian, Y., & Sargent, A. C. (2021). The gendered pandemic: The implications of COVID‐19 for work and family. Sociology Compass, 15(6), e12881. doi:10.1111/soc4.12881.

- Log in to post comments